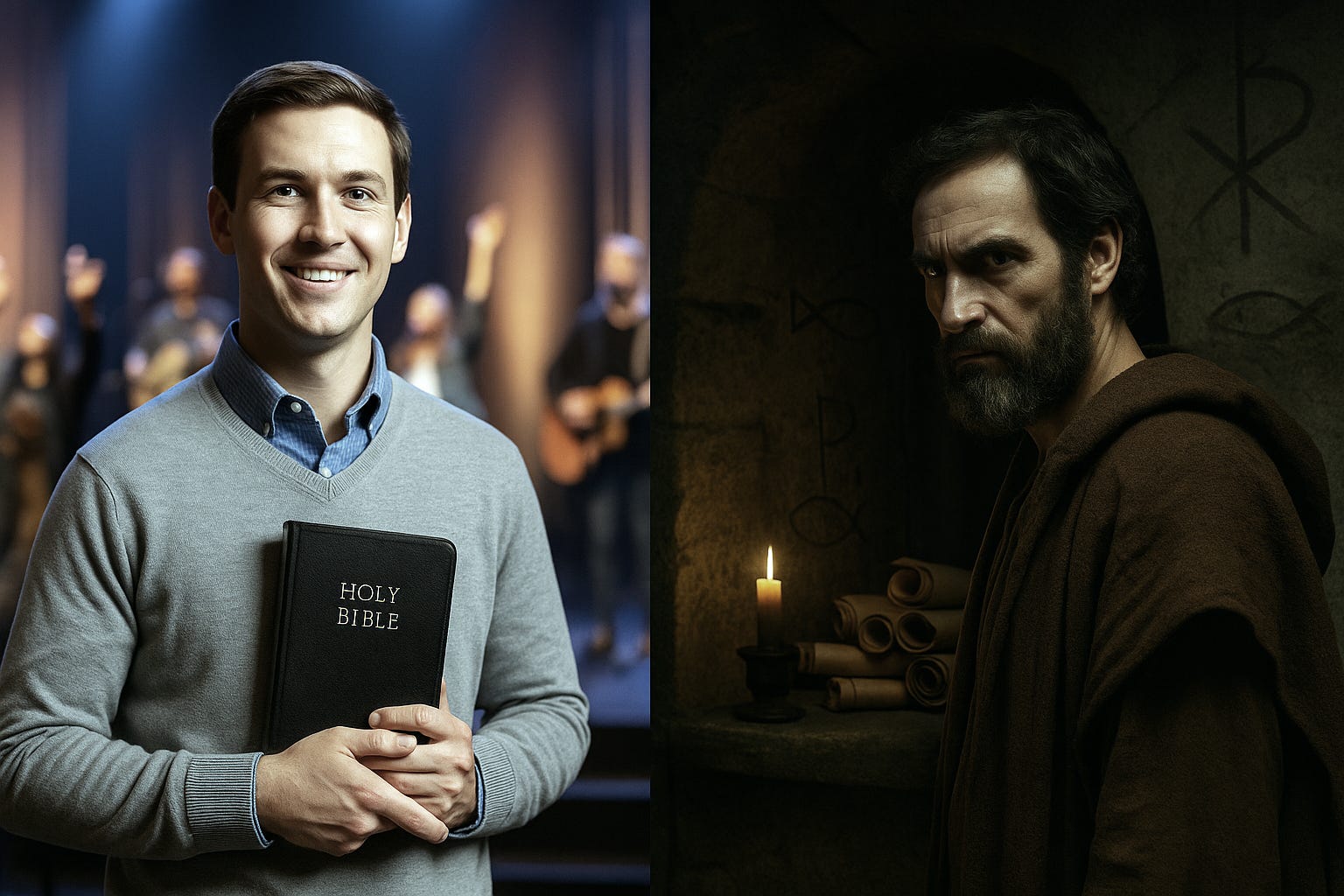

Time-Travel a Christian to 300 CE — They’d Burn for Heresy

Most of what modern Christians believe would get them kicked out, laughed at, or set on fire in early churches.

If you plucked a random Christian from today and dropped them into the year 300 CE, they’d probably be out the door and into the flames before they finished explaining the virgin birth. Why? Because most of what they think they know about Jesus, God, being saved, and even about the Bib…