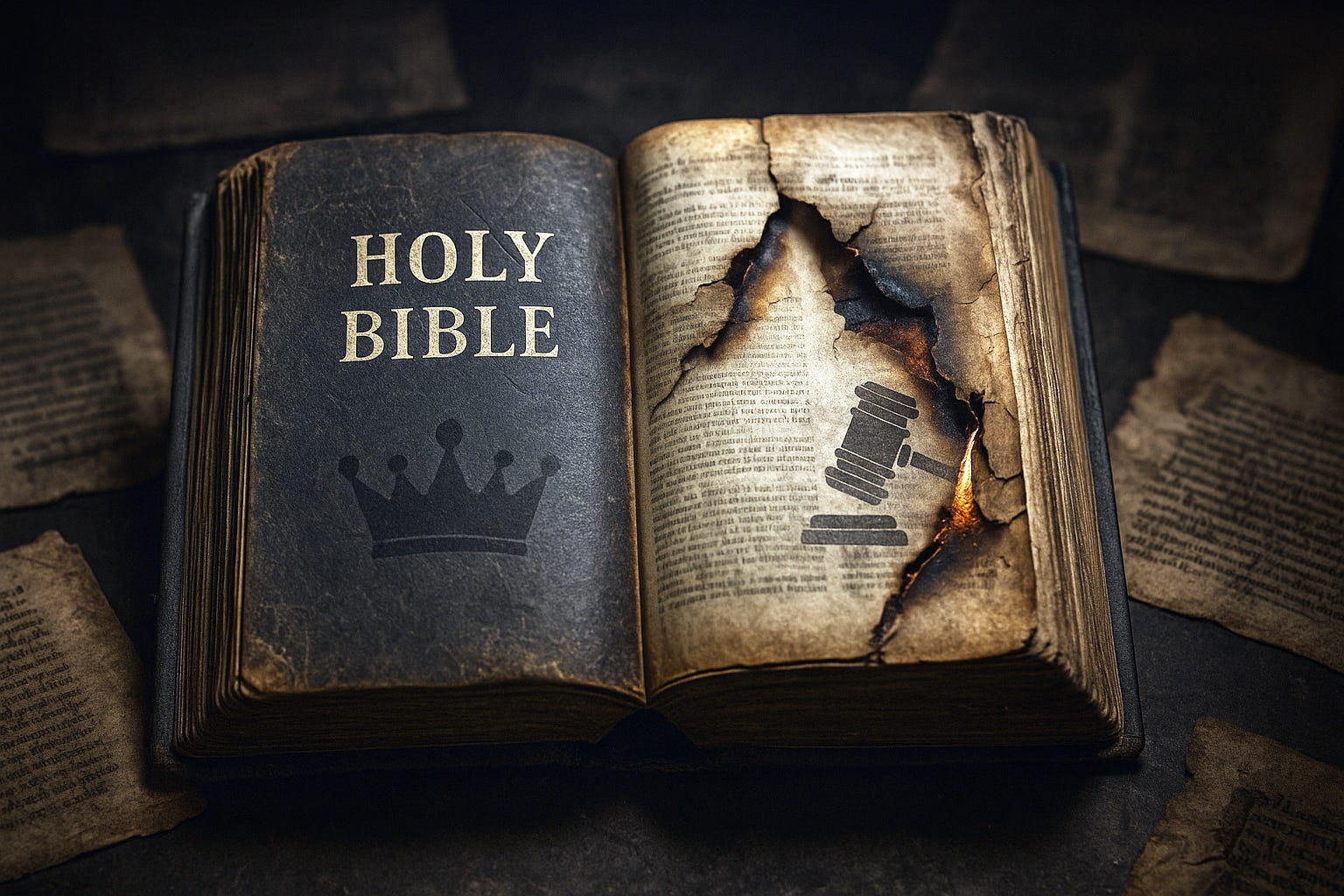

The Secret History of the Bible – What You Were Never Told

Uncover the hidden truths behind the Bible's creation, from political power struggles to the exclusion of crucial texts—what you’ve never been told about the sacred scriptures.

The Bible is widely considered the word of God by millions, but behind its pages lies a messy and controversial history that most people don't know about. It’s not just about divine revelation—it’s about power, politics, and the de…