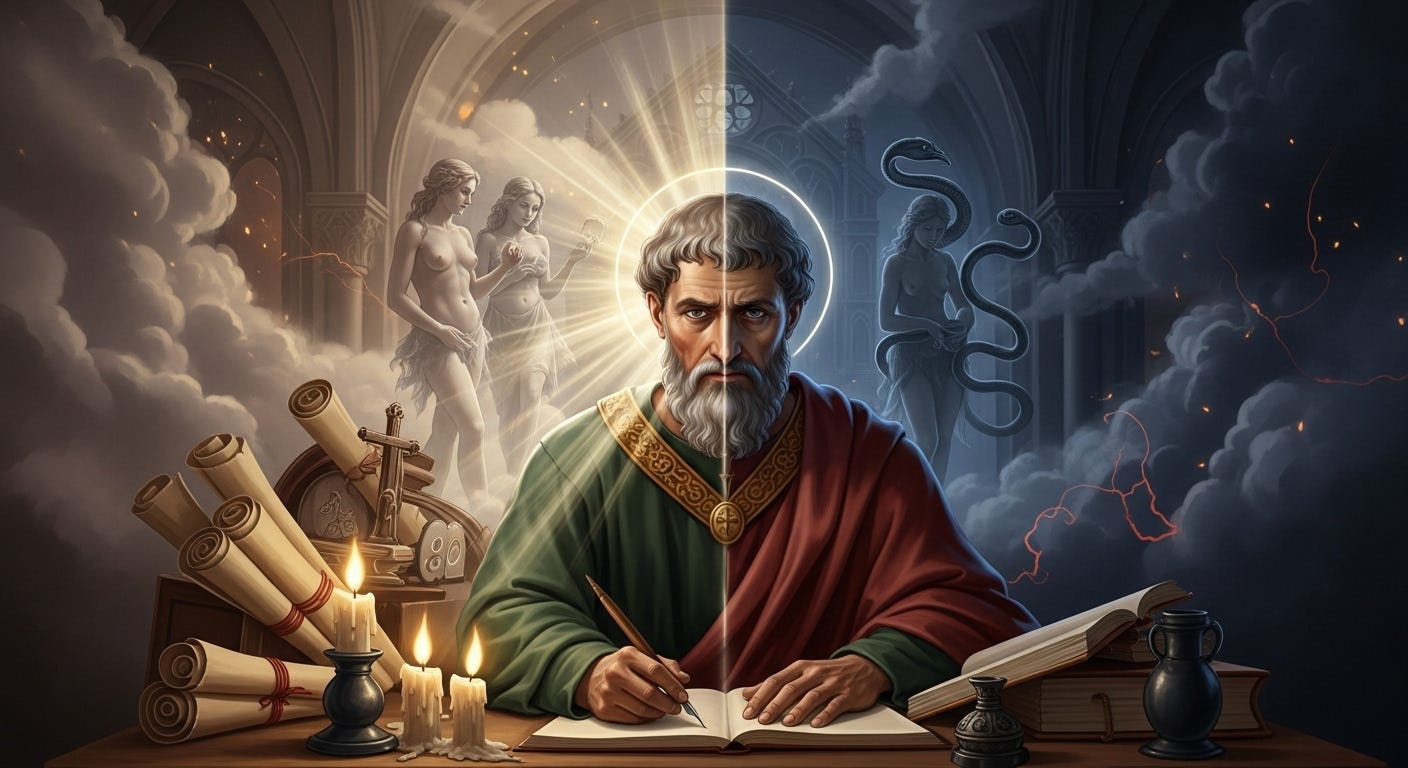

How Augustine’s Guilt Turned Christianity Into a Religion of Shame

From sex and sin to control and confession — how one man’s troubled conscience shaped the faith of billions.

Augustine of Hippo — saint, philosopher, and professional guilt machine — is one of the biggest reasons Christianity became obsessed with sin. Born in 354 AD in North Africa, he lived a life that would make most modern priests faint. He chased women, joined a heretical cult, and partied his way through his twenties. Then, after years of indulgence and i…