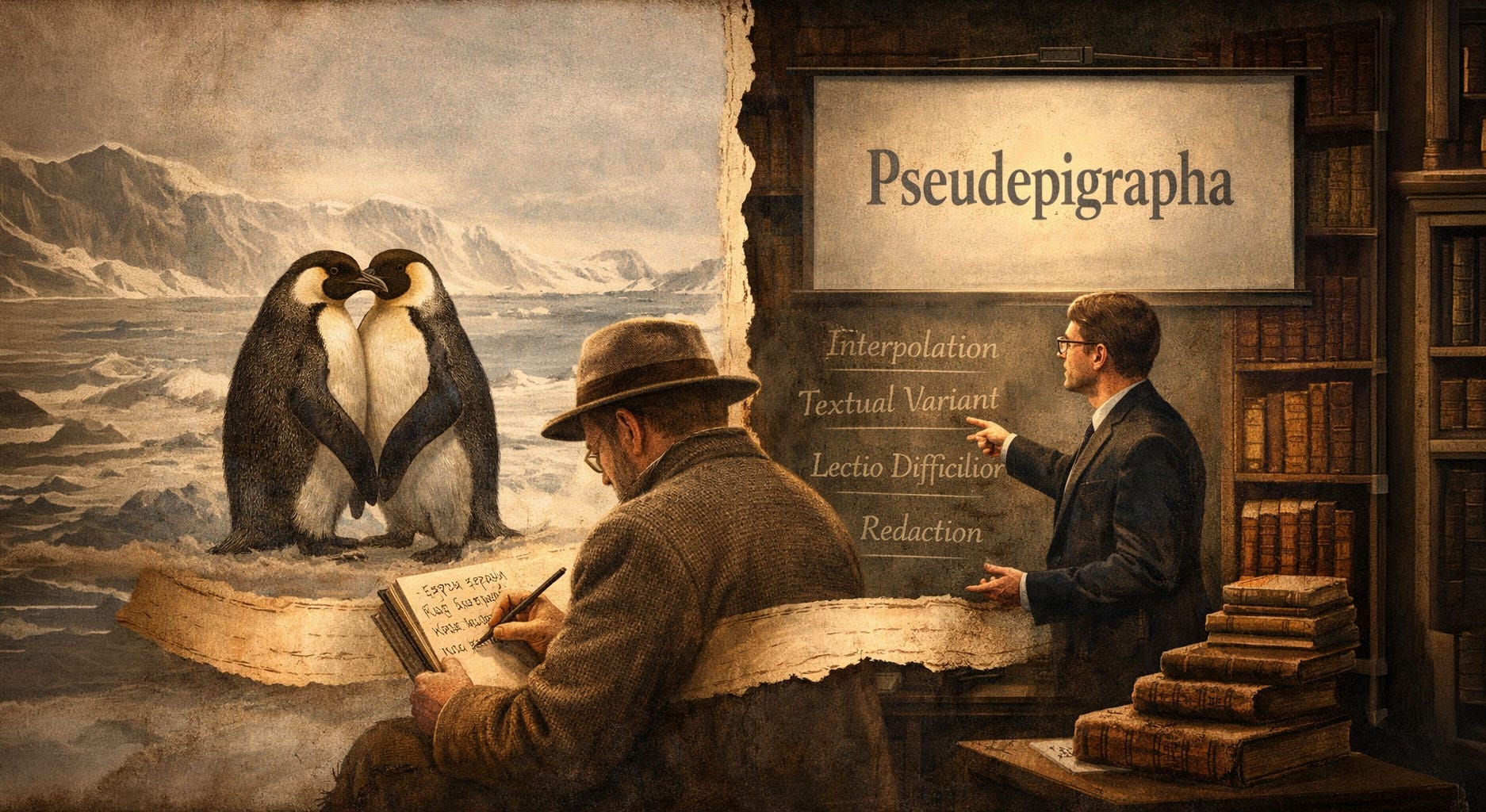

Gay Penguins and the Bible– How Scholars Hide the Uncomfortable

How far have we haven’t from the days of hiding gay penguins in Greek just to 'protect' the public?

Back in the early 1900s, British scientists studying emperor penguins in Antarctica saw something that rattled their Victorian nerves: male penguins hooking up with other male penguins. No breeding. No eggs. Just straight-up gay penguin courtship, mounting, and pair-bonding. And not just one or two flukes—this was widespread, normal penguin behavior.

So what did they do?

They panicked at the mere suggestion that homosexuality might be in nature, after all. These were men raised in a culture that saw anything non-heterosexual as depraved, perverse, or even criminal. At the time, homosexuality was illegal in Britain and across its colonies, from the Middle East to Bermuda. Just a few years earlier, Oscar Wilde had been imprisoned for it. To put things in perspective, as recently as the 1980s, part of the UK was still prosecuting gay men, that is, up until the European Court of Human Rights stopped them, not because they chose to change their laws voluntarily.

So instead of publishing their observations in plain English, these early 20th-century scientists wrote their notes in ancient Greek.

Greek. Not because they were being scholarly. Because they wanted to hide it. They didn’t want the public—or even most other scientists—to know what they had seen. It was a way of locking up the truth behind a gate only the “right” kind of educated people could pass through.

God forbid. Can you imagine what the truth could do?

More Than a Century Later, Still the Same Game

You’d think we’d be past that by now. Over 100 years have gone by. We’ve split atoms, decoded DNA, walked on the moon. Gay penguins have been on TV. There’s even a children’s book called And Tango Makes Three about a real gay penguin couple raising a chick.

But here’s the real kicker: academic scholars—especially in religious studies—are still pulling the same - what scientists would call - the ruminant digestive byproduct of a bull.

They’re not writing in Greek anymore, but they might as well be.

They bury plain facts in language so soft, so padded, so vague, that most people never hear the truth. Or if they do, it comes across as “controversial,” “up for debate,” or “unsettled”—when it isn’t.

They throw in terms like pericope, ipsissima verba, interpolatio, lectio difficilior potior, and expect you to be grateful for the confusion. It’s intellectual camouflage.

You Can’t Make This Up

I touched on scholarly language briefly—as one of the reasons I write about religion—in “Why Tanner Writes on Religion? Does He Care What You’ll Think?” But today, we’re going deeper.

Let’s start with an example to give you a taste of what biblical scholars do.

The pericope adulterae (John 7:53–8:11), although absent from the earliest Alexandrian witnesses such as 𝔓66, 𝔓75, א, B, and lacking in the canonical corpus of Origen and Chrysostom, appears interpolated from the Western textual tradition (D, ital, sy). While some MSS relocate it post-Luke 21:38, suggesting a liturgical gloss or secondary assimilation, the nomina sacra remain consistent with Johannine stylization, though internal evidence (lectio difficilior) challenges its authenticity. Consequently, most scholars consider it an instance of interpolatio ex traditione ecclesiastica rather than ipsissima verba Iesu.

The manuscript evidence (𝔓66, 𝔓75, Codex Sinaiticus [א], Codex Vaticanus [B], etc.)

And you naively thought English was the common language of researchers publishing papers for an international audience.

Translation for normal humans in real English:

The story of the woman caught in adultery isn’t in the oldest copies of John’s Gospel, and early Church writers didn’t know it. It shows up later, often in different places, and even though some parts sound like John’s style, it probably wasn’t part of the original. Scholars think the Church added it later, not that Jesus actually said it.

This is exactly the kind of writing that keeps truth locked away behind Latin phrases and manuscript codes, even when the core message could be said in one sentence.

They Won’t Call Forgery What It Is

Let’s talk about Christian scripture for a second. Several letters in the New Testament were forged. Not “possibly forged.” Not “debated.” Forged. As in: someone pretended to be Paul, wrote a letter under his name, and passed it off as legit.

Scholars know this. Bart Ehrman, Bruce Metzger, and tons of others have pointed this out. Even Christian scholars overwhelmingly accept this.

But instead of saying “forged,” you’ll get language like:

pseudepigrapha

Fancy way of saying “a false attribution.” A fake. Someone using a dead guy’s name to push a message. They’ll say pseudepigraphy like it’s just an ancient quirk of the genre. No. It’s forgery.

That’s like finding a fake signature on a check and calling it “a questioned scribble.”

To be fair, on a good day the intellectual honesty of scholars go as far as saying:

“The authorship is disputed.”

“Scholars question Pauline authorship.”

“There is debate around attribution.”

The biggest defense for not calling forgery what it is, is that it was very common to sign papers using the names of prestigious figures to lend authority at the time—as if that changes the definition of what was being done. Marrying girls at the age of 13 has always been child marriage, and sending boys to war as early as 12 has always been child abuse. These things might have been the norm back then, and we can judge the people accordingly, but that doesn’t make what happened okay or any less traumatic for the children.

Wouldn’t it be whitewashing history if we avoided the term slavery, just because it was once common - the norm- for white men to enslave Africans, even among the founders of the United States?

Anonymous Gospels Aren’t a Guess—They’re a Fact

The four gospels in the Bible? Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John?

Their names were slapped on decades after the fact.

They were originally anonymous. No author names. No autographs. No introductions like “I, Matthew, saw this with my own eyes.” Nothing. Just the story.

Church leaders later assigned the names to give them authority. That’s not a theory—it’s historical fact. Facts that even Christian scholars overwhelmingly accept, including those in studies funded by the Catholic Church.

But if you really want to confuse the average John and Jane, call it anonymity in the canonical Evangelia, or better yet, say the texts were written by redactors in the Matthean tradition. Just never go further than vaguely stating that the traditional ascriptions are not original to the texts.

Evidence of Edits, But No One Screams “Tampering”

There’s clear evidence of tampering in the biblical texts. Whole verses added later. Stories inserted. Endings swapped. And again, this isn’t hidden knowledge. Every major edition of the Bible today admits it—quietly—in the footnotes.

The story of the woman caught in adultery? Not in the earliest manuscripts.

The last twelve verses of Mark? Also missing in early versions.

1 John 5:7—used for the Trinity? Straight-up forged and added in the Middle Ages.

But scholars don’t call it “tampering.” They use phrases like:

“Textual variants.”

“Later interpolation.”

“Scribal additions.”

Or more Greek: glossa, interpolatio ex traditio, harmonization, Western non-interpolation. They’ll tell you it’s a “Western text-type phenomenon” or “an example of secondary redaction,” but they won’t just say: “Someone altered the text.”

It’s like saying someone broke into your house and rearranged the furniture—but instead of calling the cops, you just shrug and say “Well, that’s a decorative variant.”

Why the Lack of Courage?

Why are religious scholars so afraid of just saying things plainly?

Because they know how fragile belief can be when exposed to blunt facts.

They know that if the average believer heard that:

Paul didn’t write half the letters in his name,

the gospels have no known authors,

and the Bible has been altered and edited repeatedly...

...they’d panic. Or worse, they’d start asking questions. Dangerous questions. Questions that might unravel the whole sweater.

So instead of giving people the truth straight, they tiptoe. They soften. They dilute.

They act like facts need to be whispered, like a penguin mating with another penguin in the Antarctic fog.

And they add just enough Greek and Latin to make sure only insiders understand. Sola scriptura, ipsissima verba, formgeschichte, source criticism, traditio-historical method. Pick your poison. It’s all packaging for the same cowardice.

Knowledge Shouldn’t Need a Permission Slip

Religion is one of the most powerful forces in human history. It has shaped laws, wars, sex, power, guilt, family, identity, morality.

It tells people what is sacred. What is forbidden. Who they are.

And yet when it comes to studying religion? We treat it like it’s too precious to touch.

Like truth needs a permission slip from the church. Like academics must translate it into Greek to keep the general public from reading it.

But this isn’t 1910 anymore. We don’t need gatekeepers to protect us from gay penguins or forged scriptures.

We need honesty.

We need clarity.

And we need scholars who aren’t afraid of religious institutions calling them names.

Truth does not require protection. If a belief system cannot withstand scrutiny, then the fault lies not in the questions, but in the system itself— Dr. Francesca Stavrakopoulou, God: An Anatomy

Do People Deserve Comfort or the Truth?

This is the real fight. It’s not science vs. religion. It’s not atheists vs. believers.

It’s comfort vs. truth.

A lot of people want comfort. They want to think everything they were taught as kids is true. That their grandma’s Bible is flawless. That their church would never lie.

And scholars—especially religious ones—feed that comfort. They don’t want to upset Grandma. They don’t want to lose their jobs. So they hedge. They soften. They speak Greek.

But the rest of us? We want the truth.

Even if it’s ugly.

Even if it breaks something.

Because broken illusions are better than beautiful lies.

“Faith that depends on ignorance is not faith—it’s manipulation.”

— Dr. Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus

What on Earth Do Penguins Have to Do With Scripture?

Everything.

That early 20th-century decision to write the truth in Greek was about shame. It was about fear. It was about control. It was about deciding the public couldn’t handle the facts.

And that’s exactly how too much of religious scholarship still works.

Don’t tell people Paul didn’t write that.

Don’t tell them Mark ended at 16:8 with no resurrection.

Don’t say forgery.

Don’t say anonymous.

Don’t say altered.

Just keep it soft. Keep it vague. Keep it safe.

That’s not scholarship. That’s not courage. That’s cowardice—decorated with Latin endings and footnotes that no layperson will read.

Last Thoughts

If you’re going to study the foundations of human belief—where people go when they die, who they should love, how they should live—you’d better do it with guts.

No more Greek. No more footnote games. No more word soup.

Call forgery, forgery.

Say anonymous when it’s anonymous.

Say tampered when it’s tampered.

Tell people the truth, not because they’ll like it, but because they deserve it.

Gay penguins exist. So do forged Bible verses. And the truth will still be true whether you whisper it or speak it openly.

To be honest, only a small portion of subscribers are paid—most of my posts, including this one, are free for everyone to read. But reader support buys something priceless: time. Time to research, question power, and hold the powerful accountable. If you can afford it, your support helps keep this work alive.

"Because broken illusions are better than beautiful lies." Thank you. Richard Rohr talks about the " sin of certitude". Maybe there is alot of faith deconstruction because our leaders were afraid we could not handle the truth and we found out. Here is a 30 sec speeh by RR on this subject.

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/FOZRz0ab5Jc