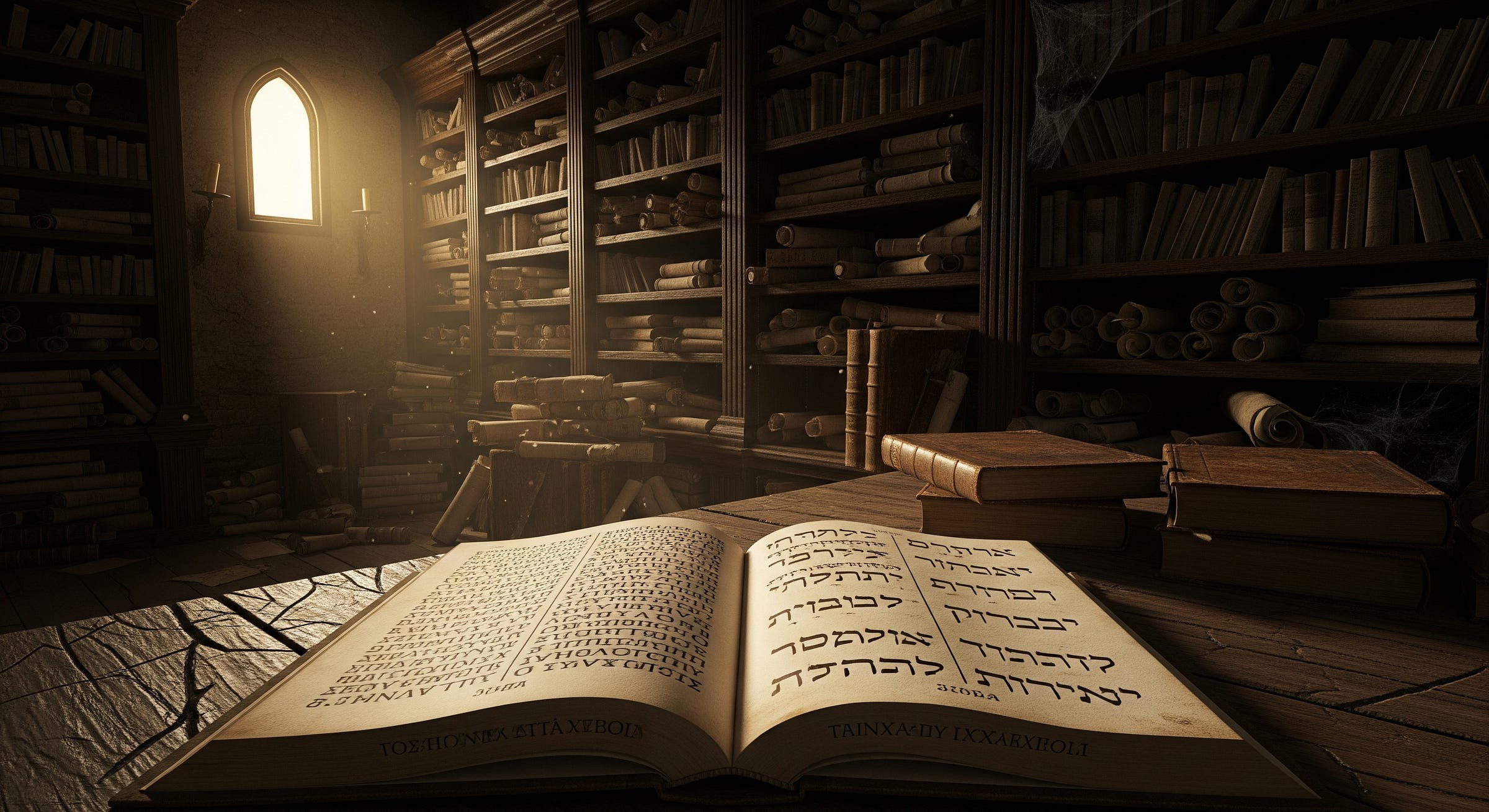

Bible’s Forgotten Books They Don’t Want You to Read

How entire texts were left out of your Bible — and why most churches don’t want you asking questions about them

When most Christians pick up a Bible, they think they’re holding the complete word of God. That’s what churches have told them all their lives — this book is the book, nothing missing, nothing extra. But the truth is, the Bible is a carefully cura…