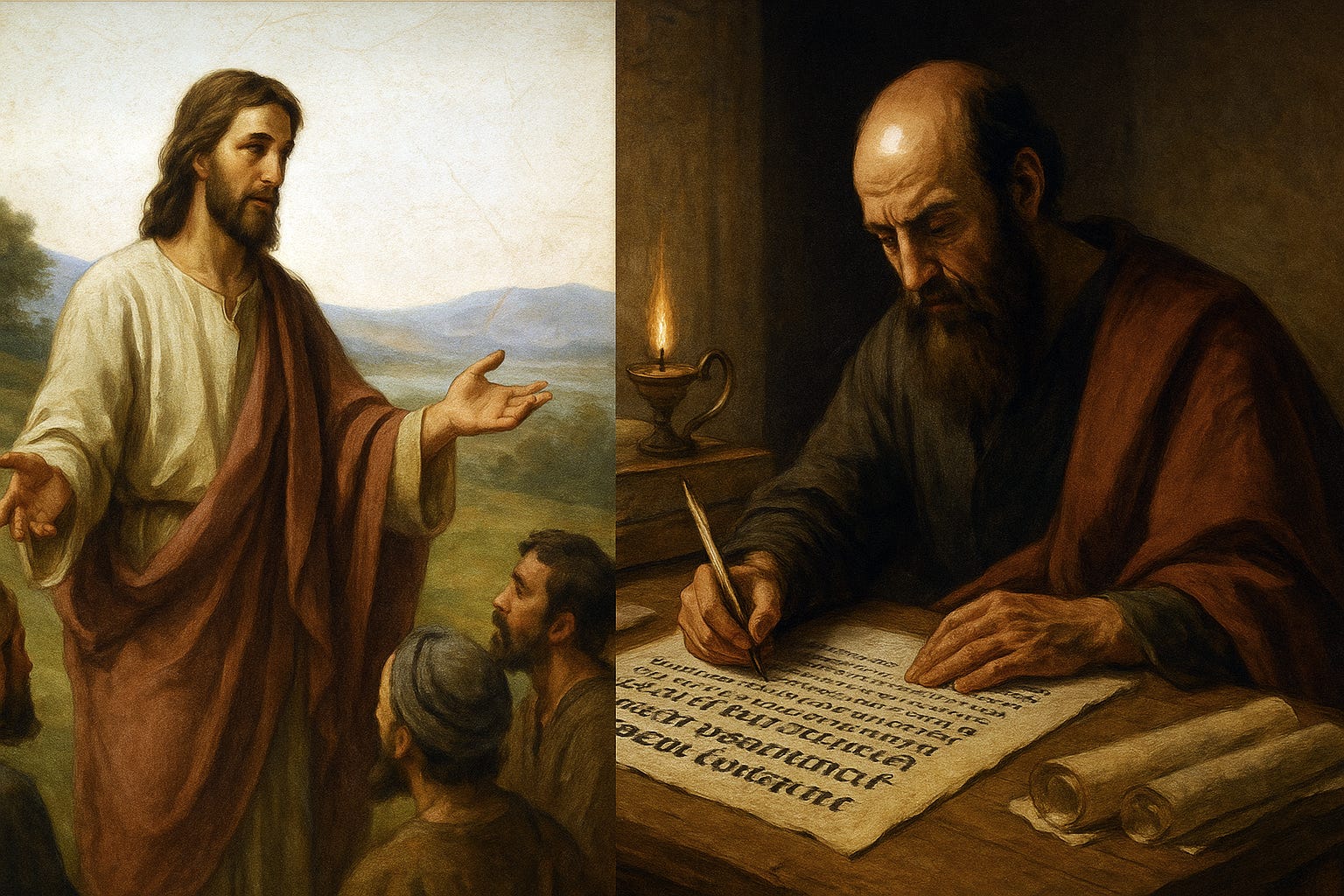

8 Doctrines Paul Invented Out of Thin Air

How the Apostle’s inventions replaced Jesus’ message and rewrote Christianity’s core beliefs

If you read the Gospels and then jump straight into Paul’s letters, you’ll notice something strange. It’s like you’ve walked into a completely different religion. Jesus spends most of his time teaching about God’s Kingdom, compassion for the poor, loving enemies, and k…